FIEGLHUBER-GUTSCHER IN THE CONTEXT OF THE ART OF HER TIME

Cornelia Cabuk

“Light-hearted and unnoticed by the art of today, by the art of the past, I try to bring what I see to the canvas without flattery (…).[1]

The statement by Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher in 1930 testifies to the unbroken self-confidence of the 46-year-old artist, but also to her conviction that she was undeterred in following the artistic path she had taken. In view of the disadvantages due to her gender in her profession as a painter and graphic artist, which she experienced when she was born in the same year as Oskar Kokoschka in 1886, the consistency she showed in pursuing her artistic career is astounding.[2] At the peak of her career, when she showed her work in a show at the renowned Würthle Gallery in 1935, the writer Paul Stefan characterized her in a review of the exhibition in the daily newspaper "Diestunden" as a "well-known painter" who, "inspired by Kokoschka and Faistauer “, in which nude painting would go its own way.[3] However, he did recognize her talent as a painter: "The coloring shows a special taste, the performance in general shows rich skill."[4] Critics such as Arthur Roessler and Adalbert Franz Seligmann usually denied the originality of women and only sought their quality in the successorship of male artists.[5] If you look at the work of Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher in relation to male colleagues, you can see one of course in the subjects as well as in their understanding of color as an essential factor of the the artistic intrinsic value of the pictorial space.

Professionally, she was firmly anchored in the scene for women's art in Vienna and regularly exhibited in the Association of Female Artists. These presentations of female art often took place as guest exhibitions in the large artist associations Secession and Hagenbund, in which women were not accepted as members. Soon after studying from 1904 at the Art School for Women and Girls in Vienna, founded in 1897, which she graduated in 1912, she became known as an important graphic artist and took part in the international book trade and graphics exhibition in Leipzig in 1914. In 1917 her work was shown as part of the Association of Female Artists in Stockholm, and her name also appears in the exhibition "German Women's Art" by the Association of Female Artists in the Künstlerhaus in Vienna.

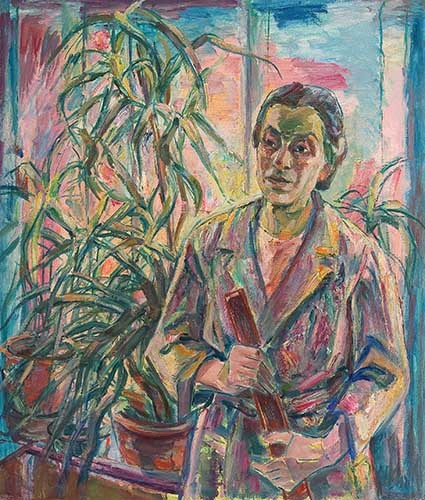

One could say that Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher continued to pursue the goal of bringing her perspective to the screen. This professional security, which was not least promoted by the solid technical training at the art school for women and girls, is shown, for example, in the "Self-portrait in the painter's coat", which deserves attention as a remarkable example from the series of her unsparing self-portrayals. The attentive gaze and the harsh, unembellished features expressively characterize her as a well-established artist personality at the age of 38, who showed herself self-confidently as a painter in front of the window looking out into a garden. The flesh tones of the skin and the white coat reflect the bright garden section with trees in impasto pastel tones, with cool blue tones dominating. The light-filled, two-dimensional application of paint and the intrinsic painterly value of the individual shades refer to her knowledge of French Post-Impressionist painting, which impressed her on her study trip to France in 1913. Her progressive teacher at the Kunstgewerbeschule, the "Ursecessionist" Maximilian Kurzweil, was also influenced by French painting, and it seems like a belated homage to him that in her self-portrait she used his famous portrait of Therese Bloch-Bauer in the depiction of her easy almost quoted with an open mouth. Her portrait "Fräulein Z" is also reminiscent of the high level of Kurzweil's French-style painting culture, with the fine psychological interpretation, especially of the children's portraits of teachers and students, appearing in unison with a slightly melancholic nostalgia. The stronger emphasis on texture and colorful orchestration in the strong red-white-green chord show their independent development from fin-de-siècle nobility to expressive individualism. The tendency to empathetically reproduce a mood of self-reflection and great painterly skill in mastering tone-on-tone painting characterize her portrait of a smoking man, for which she also took the French painting in Édouard Manet's Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé (1876, Musée d'Orsay, Paris) in mind.

Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher had already emerged as a self-confident and successful artist during her studies as an assistant to Professor Michalek and as a member of the Vienna Artists' Etching Club. Participation in the guest exhibitions of the Austrian Association of Female Artists in the Secession and in the Hagenbund confronted her with the latest developments in the field of contemporary painting. While the Association of Women Artists in Austria was striving to establish itself as a so-called “female Secession”[6] in contemporary art as a progressive ideal, the Hagenbund represented increasingly more radical currents. Since Fieglhuber-Gutscher's teachers at the art school for women and girls came from the Secession environment, the reform movements of the turn of the century formed the progressive teaching content. The openness to foreign art movements, such as post-impressionist tendencies in France, was an essential aspect of her varied education. The special exhibition Painting and Sculpture in the rooms of the Hagen Artists' Association in 1911[7] with members of the new art group around Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka possibly led to a paradigm shift for the 25-year-old artist towards Expressionism. Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher now devoted herself primarily to painting. Impressed by the striving for individual expression and the expressive colorism, she chose her future teacher Robin Christian Andersen from this circle. She also dealt with the impetuous, irrepressible colorfulness in Anton Faistauer's early work. Andersen and Faistauer set out together for Monte Verità near Ascona in 1909/10 and belonged to the young avant-garde around Egon Schiele. A crucial content of the life reform movements of this time was the equality of men and women. Andersen and Faistauer were with Schiele's New Secession, the Sonderbund and the Wassermann Artists' Association in Salzburg. The painter Broncia Koller-Pinell played an important role in the New Secession (based on an idea by Egon Schiele). Koller had already taken part in the Secession exhibitions, the two art shows in 1908 and 1909, and had a highly acclaimed solo exhibition in the Miethke Gallery. In the portraits "Portrait of a Lady" and "Fräulein Z", Fieglhuber-Gutscher, like Koller, combined the stylization tendencies of Art Nouveau in some female portraits with a finely graduated palette that reflected the mood of the protagonists.

With regard to the choice of their teacher Andersen, who with his colleagues from the Sonderbund in the VI. Kunstschau exhibited in the Künstlerhaus from April to June 1925,[8] Fieglhuber Gutscher's painterly work during this period can be viewed as a deliberate parallel action to this decisive presentation of a male-dominated avant-garde. However, Broncia Koller also took part in the art show, in which u. a. Works by Egon Schiele and Otto Rudolf Schatz were shown. In the autumn of 1925, the fundamentally important exhibition of the Association of Female Artists "German Women's Art" took place in the Künstlerhaus, an impressive showcase of female artists, including works by Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher. It was the last joint show before the "radical" wing of the Association of Female Artists split off under Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka with the spatial artists in Vienna's women's art.[9] Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher was not one of these, but remained in the association of female artists, but in her painting she showed interest in modernism as a phenomenon in the form of expressive colorism, as represented by Andersen and Faistauer. Her portrait of a "lady in green" in a very free, virtuoso style of painting with an impasto, flat brushwork of shimmering, bright, rich colors can be interpreted as a female answer to their masculine point of view.

The typeface of her signature proudly approximated that of Faistauer, knowing that she had created an adequate counterpart to his color sensualism. The cheerful, slightly ironic facial expression of the sitter seems to underline this fact. This expression of cheerful and ironic distance as a subversive reaction to masculine dominance in the art world shaped the ceramics of Viennese women's art in a similar way in the women's heads by Vally Wieselthier and Gudrun Baudisch.[10] Irrespective of this, Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher deepened her interest in the world of women from a female perspective in the years that followed. A state of restrained, passive observation of the outside world and a touch of melancholy as in Picasso's blue period characterize the "Three Women on the Balcony". Luminous, changing shades of red, violet and green lend the everyday scene at the window a festive, almost symbolic character.

The next step in the consequence of the professional career she pursued as an artist was her show in 1935 at the Würthle Gallery. Since 1919 Lea Bondi-Jaray had established a program geared towards contemporary modernism with Herbert Boeckl, Anton Faistauer, Alfred Wickenburg, Carry Hauser, Jean Egger, Oskar Kokoschka and Otto Rudolf Schatz. After all, artists like Vilma Eckl, Hilde Exner, Hilde Goldschmidt, Lilly Steiner and Lisel Salzer were among the exhibitors.

Informal poses of natural physicality characterize Marianne Fieglhuber Gutscher's nudes, such as the two figures leaning against each other in the picture "View into the Open". The unmediated view of the female body is astounding in the seemingly randomly selected image detail, in which the legs and the right-hand figure are partially cut off from the picture frame. The title deals with a variation of Schnitzler's novel Der Weg ins Freie, whereby the women depicted in the picture indirectly perceive a view of nature through a hand mirror. Hardly chosen by chance by the well-read artist, the urge for freedom addressed in it also has an effect in the impasto brushwork in the substantial red-blue chord of the pictorial space, which she also reflects in the different tones of the flesh tones. Her movement study of the dancer Kaufmann shows in the modern figure language and the conception of corporeality similarities with the representations of women by Franziska Zach, who was an extraordinary member of the Hagenbund and exhibited at the Wiener Frauenkunst after 1925. The motif "Reading in front of a river landscape" shows the ideal of connection with nature and intellectual education. In contrast to Faistauer's and Kolig's depictions of nudes, in the picture "Akt mit Blumenvase" she characterizes an almost life-size image of a decidedly female perspective, which is reminiscent of the feminist body images of Paula Modersohn-Becker. However, it is not an adapted primitivism that explains the modernity of this painting, but rather the expressive, luminous coloring, which in shimmering tones represents a counter-image to Faistauer's and Kolig's erotic depictions of nudes. In contrast to these, the color space appears as part of the figure's natural aura and as her organic field of activity. The liberal mentality expressed in these women's pictures and their decidedly modern painting style found no official recognition in the following years of Austro-Fascism and the Nazi dictatorship. Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher, who practically "put away" patriarchal family relationships and a conservative social environment, was severely affected in her professional understanding by the conformity of the Association of Female Artists under National Socialism. It was the beginning of a development that brought about the erasure of her artistic position as a female modernist. Through the forced flight, exile and racist persecution of a significant number of her friends in the Association of Female Artists and Viennese Women's Art, she assumed fatal proportions.[11]

Fieglhuber-Gutscher's "Self-Portrait with Cigarette" from this time shows her in her multiple burdens as an artist, housewife and mother. An escapist tendency towards abstraction can be seen in the glowing background colors alone. Her career dream seemed over because the Nazi authorities classified her as “on the wrong track” and prevented her from exhibiting. The threatening leafy plant, which makes the "woman in the black armchair" appear small, can hardly be surpassed in its negative symbolism and reflects the sense of an existential crisis in the time of the Second World War. The “Self-Portrait in a Red Jacket” shows her in the mental state of inner emigration. Only in the self-portrait "Woman at the Garden Door", which she painted soon after the end of the war, does Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher make a cautious new beginning based on her artistic successes in the 1930s. She emphatically pushes open a door that reveals an abstract landscape in light, carefree colors. In order to counteract the oblivion of female artistic creation, she began to send her constant applications for admission to the Künstlerhaus, whose constant rejection was accompanied by her unimpressed, tireless artistic work. Only when she was over 80 did her retrospectives take place in the Neue Galerie Graz at the Universalmuseum Joanneum in Graz in 1974 and 1979, and in the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in 1977. In 2020/21 her work was shown in the group exhibition "Ladies first! Female Artists in and from Styria 1850-1950" in the Neue Galerie Graz at the Universalmuseum Joanneum. In her rich late work, her motifs, including the impressive character portrayals of her family members, are transferred into a sphere of timelessness through the irrepressible colorism of a translucent colourfulness, detached from the art of today, from the art of the past.

[1] Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher quoted in: Otto Hans Joachim, M. F-G., in: Österreichische Illustrierte Zeitung, Volume 40, H. 11, March 16, 1930, p. 7.

[2] On the largely forgotten careers of female artists in Austria: Julie M. Johnson, The Memory Factory. The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900, Purdue University 2012; Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, Women Artists in Austria 1897-1938, Vienna 1994.

[3] Paul Stefan, exhibitions in: The hour, 18th year, H. 8633, 19.4.1935, p. 5.

[4] ibid.

[5] Vgl. Megan Brandow-Faller, The Female Secession. Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women´s Academy, Pennsylvania 2020, S. 81.

[6] Hans Ankwicz-Kleehoven coined the term; Brandow-Faller, as note 5., p. 2.

[7] Special exhibition painting and sculpture in the rooms of the Hagenbund, exhibition cat. Vienna February 1911.

[8] XLVL. Annual exhibition of the cooperative of visual artists in Vienna. VI. Art exhibition of the Association of Austrian Artists, Künstlerhaus Vienna April-June 1925.

[9] Megan Brandow-Faller, An Art of Their Own. Reinventing Frauenkunst in the Female Academies and Artist Leagues of Late Imperial and First Republic Austria, 1900-1930, Diss. Phil. Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. 2010, p. 355.

[10] Brandow-Faller (like note 5), pp. 147-155.

[11] Unfortunately, the masculine-dominated art history of the post-war period has also promoted the oblivion of the artistic achievements of these women. See Johnson (as note 2).